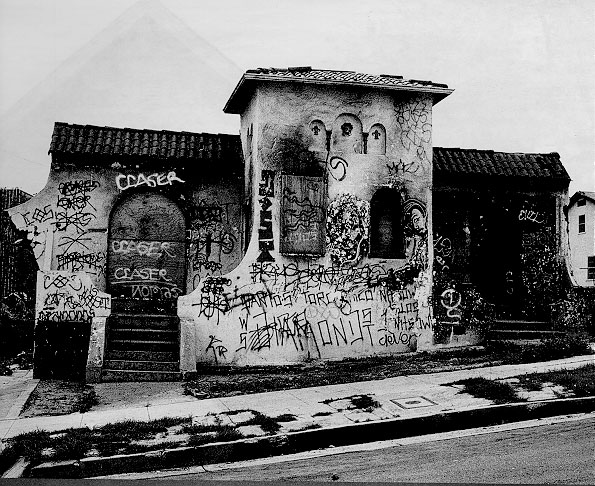

| Historically, buildings were constructed around what architects call "program," the specific uses to which a building would be put. And certainly we still often construct buildings for specific purposes--Olympic cities like Atlanta, for example, frequently construct spaces for specific athletic events. But increasingly we build spaces with multiple programs or systems of use. Consider the meeting rooms of this hotel, which today house academics talking in urgent tones about writing but tomorrow--or even in two hours--might witness pest control experts speaking excitedly about new technologies for termite treatment or Internet market analysts debating demographic measurement techniques in the age of the World Wide Web. Or, to consider the more famous example, the numerous contemporary art museums that also host wedding receptions and charity fundraisers in the evening. In the Eisenman study in the handouts, Eisenman layers--in another form of superimposition--a series of histories of the site of proposed art museum, projecting into the future. In an ironic way, the burned out, tagged house in the picture just above (taken from piece called "Ozzie and Harriet in Hell") is shifted violently from a structure for familial living to a violent commentary on the decline of the promise of suburban living. |

Davis, suburban blight (from Davis, "Ozzie and Harriet in Hell") |

Eisenman, Program Sketch for University Art Museum mapping program across history/future, Cal State Long Beach (from Jameson, Seeds of Time) |

The juxtaposition of events in spaces, then, provides another method for shock in information saturated societies. In composition, we sometimes witness this crossprogramming for a brief instant in the gradual breakdown of genres, in which a single text takes on characteristics of narrative, of visual design, of advertisement. But such exceptions are relatively rare. If we want to think about cross-programming, we must do more in the way of allowing our students--and ourselves--to make textual spaces function in multiple ways, across time and event. For composition, as it's currently considered, the space is the event. But if we consider texts as spatial in a more complex way, we will find room for multiple events to take place in the same space at different times. This perspective provides one reading of MOO spaces, where a single portion of the text (such as the garden Teddi Fishman built in tMOO at Purdue) hosts a number of different events, ranging from class discussions to private work to group meetings. In each event, the architectural space is related to but does not determine the specific meanings being made in the space. |