Starting the Discussion

How Money Talks in Cartoons

How Money Talks in Cartoons

Klein,

pp. 91-145

- OK, so how does

money talk in cartoons? What's the relationship between what is produced and

the funding? How does the money determine what we see?

- "It was indeed a buyer's

market on all levels [in 1936]," according to Klein. What does this mean

in practical terms?

- Also in the mid-thirties, costs

were rising as cartoons were being repackaged. What was changing? How did

this involve such things as storyboarding and pencil tests?

- Define "full animation."

- What does Klein's watercolor find

(described on p. 96-97) tell us about life at the Disney studio in this period?

How does that contrast with the recollections of Bill Melendez?

- "It is curious," Klein

notes, "that so much investment in animation resulted in a much tamer

cartoon." Then he sums up, "Corporatizing cartoons tends to remove

those elements that make the animation surprising or funny." How do these

comments echo some of the observations of Richard Schickel?

- If "media must be studied

by the evidence of how an audience remembers (entertainment, leisure, personal

details, history, politics)," then what great shift, underway in the

1930s, is still evident in our contemporary culture?

- A paradox: "Cartoons are

timeless because they look--and feel--like the year they were made."

Explain.

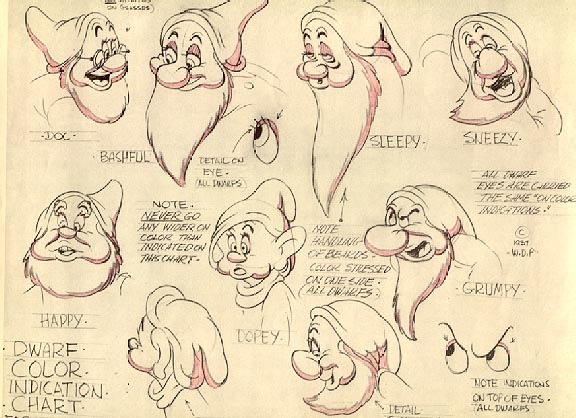

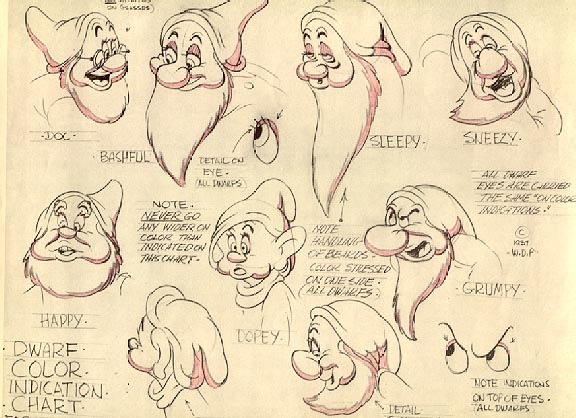

- In Chapter 10, Klein focuses on

three cartoons which he considers to be transitional between the anarchic,

graphically-defined world of primarily silent cartoons and the new "full

animation," particularly associated with the Disney studio. Though you're

not seeing this trio, the text gives a full description, so you should be

able to understand this shift in style from it. As you read, jot down what

makes each cartoon "transitional."

- What, according to Klein, is the

full animation alternative to graphic narrative, with its flat surfaces?

- For a story man at Disney in the

late 1930s, what did it mean to be required to take a very moralistic view

of the state of the world? What are some of the rules of screenwriting that

flow from that requirement? How do the final scenes of Snow White

serve to illustrate what this means?

- Can you see any clues in American

culture of the period to account for the shift from the swashbuckling melodrama

of the early 1930s to the more family-centered melodrama of the mid to late

decade?

- How is the directive to "Work

hard, stay pure, show some mechanical ingenuity, but still know your place;

then the cosmic Fates of capitalist justice will help you rise" related

to the melodramatic concept of "poetic justice"?

- How do "cautionary cartoons,"

such as the Fleischer's Cobweb Hotel, fit into this scheme of things?

- How does Klein see Popeye as prediction

of things to come, particularly in the Warner Brothers' cartoons of the 1940s?

- Just to check your reading, how

many cells were actually produced for Snow White? How many made it

into the finished product?

- Klein sees the scene with Snow

White in the forest as "one of the last times Disney used thirties metamorphosis

and animism," yet it is also a prime example of the new style of full

animation. How does this work?

- How does the phrase, "she

was born to clean," point to one of the shifts between an old model of

female perfection (Betty Boop) and the new, post-depression one? How could

we see Snow White's personality as in some sense standing in for "the

cult of childhood innocence in the late thirties"?

- In Snow White, Klein

sees three conflicting media fighting for the same space at the same time;

what are they?

- The chapter concludes: "Disney

with Snow White began the process that eventually mixes consumer

memory with urban planning. He pioneered the complete intersection between

electronic media and architectural space that we all know very well today."

Explain.

Back

to Home Page

How Money Talks in Cartoons

How Money Talks in Cartoons  How Money Talks in Cartoons

How Money Talks in Cartoons