In a review in

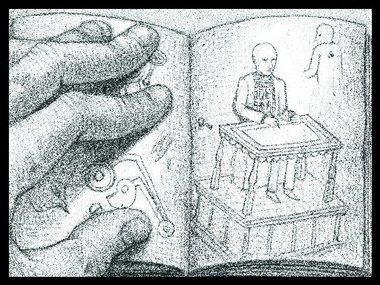

The New York Times, Manohla Dargis sees Scorsese as locating "plenty

of cinematic poetry here, particularly in the clock imagery, which comes

to represent moviemaking itself. The secret is in the clockwork, Hugo's

father says to him in flashback, sounding like an auteurist. Time counts

in Hugo, yes, but what matters more is that clocks are wound and

oiled so tht their numerous parts work together as one. The movie itself

is a well-lubricated machine, a trick entertainment and a wind-up toy, and

it springs to life instantly in a series of opening aerial shots that plunge

you into the choreographed bustle of the train station."

![]()

![]()